Suite – A set of pieces that are linked together into a single work. During the baroque period, the suite usually referred to a set of stylised dance pieces.

Partita – Baroque term for a set of variations on a melody or bassline.

Short interview I came across with Murray Perahia where both him and the interviewer come to agree that a partita is essentially the same as a suite. Also interesting to note how some movements evolve over time, e.g. the Sarabande was once a fast dance and considered almost lewd and lustful and banned at some point before becoming the slow stately dance that we are more familiar with.

Murray Perahia on Bach’s Partitas (Murray Perahia Interview)

http://imslp.naxosmusiclibrary.com/stream.asp?s=167137%2Fimslpcomp01%2Feg4521%5F001

(Accessed 24/04/18)

Variations – Form that presents an uninterrupted series of variants (each called a variation) on a theme; the theme may be a melody, a bassline, a harmonic plan, or other musical subject.

Fugue – (from Italian ‘fuga’, “flight”) composition, or section of a composition in imitative texture that is based on a single subject and begins with successive statements on the subject in voices.

Cantata – (Italian, “to be sung”) 1. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a vocal chamber work with continuo, usually for solo voice, consisting of several sections or movements that include recitativo and arias and setting a lyrical or quasi dramatic text. 2. Form of Lutheran church music in the 18th century, combining poetic texts with texts drawn from chorales or the Bible, and including recitatives, arias, chorale settings, and usually one or more choruses.

Concerto – (from Italian concertare, “to reach agreement”). 1. In the 17th century, ensemble of instruments or of voices with one or more instruments, or a work for such an ensemble. 2. Composition in which one or more solo instruments, or instrumental group, contrasts with an orchestral ensemble.

Concerto grosso – Instrumental work that exploits the contrast in sonority between a small sample of solo instruments (concertino), usually the same forces that appeared in the Trio sonata, and large ensemble (ripieno or concerto grosso)

Sonata da camara or chamber Sonata – Baroque Sonata, usually a suite of stylized dances, scored for one or more treble instruments and continuo.

Sonata da chiesa or church Sonata – baroque sonata, baroque instrumental work intended for performance in church, usually in four movements slow-fast-slow-fast and scored for one or more treble instruments and continuo.

Oratorio – Genre of dramatic music that originated in the 17th century, combining narrative, dialogue, and commentary through arias, recitatives, ensembles, choruses, and instrumental music, like an unstaged opera. Usually on a religious or biblical subject.

Mass (from Latin missa, “dismissed”) – 1. The most important service in the Roman church. 2. A musical work setting the texts of the Ordinary of the Mass, typically Kyrie, Gloria, credo, sanctus, and Agnus Dei.

Chaconne – Baroque genre derived from the chaconna, consisting of variations over a basso continuo.

Canzona (Italian ‘song’) – 1. 16th century Italian genre, an instrumental work adapted from a ‘chanson’ or composed in a similar style. 2. In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, an instrumental work in several contrasting sections, of which the first and some of the others are in imitative counterpoint.

Passion – A musical setting of one of the biblical accounts of Jesus’ crucifixion, the most common type of Historia.

Motet (from French mot, ‘word’) – polyphonic vocal composition, the specific meaning changes over time. The earliest motets add a text to an existing discant clausula. 13th century motets feature one or more voices, each with its own sacred or secular text in Latin or French, above a tenor drawn from chant or other melody. Most 14th and some 15th century motets feature isorhythm and may include a contratenor. From the 15th century on, any polyphonic setting of a Latin text (other than a mass) could be called a motet. From the late 16th century on, the term was also applied to Sacred compositions in German and later in other languages.

Passacaglia – Baroque genre of variations over a repeated bass line or harmonic progression in triple metre.

All the above definitions have come out of the glossary in this book:

Burkholder, J. P., Grout, D. J., & Palisca, C. V. (2014). A history of western music (Ninth edition.). New York, N.Y.: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc..

Decided to listen to a partita, cantata, mass, sonata da chiesa and a passacaglia as forms I’m less familiar with.

More or less randomly I chose to listen to this Bach partita played on the piano by Murray Perahia who I had not heard of before. I like his interpretation.

Partita

Partita No. 3 in A Minor, BWV 827

http://imslp.naxosmusiclibrary.com/streamw.asp?ver=2.0&s=167137%2Fimslpcomp01%2F3885649

(Accessed 24/04/18)

The first movement, fantasia, sounds immediately like Bach: The discourse between the hands / voices, the independent but inter-related melodic lines, and the continuous stream of notes. It sounds a rather like some his 2 part inventions for keyboard.

The Allemande is rather more sedate with a little less of the ‘stream of notes’ and more articulated and phrased lines, still with this 2 voice polyphony coming through.

Corrente is a slightly livelier affair with some very articulated playing with contrasts of legato and staccato in the lines.

Sarabande is a gentle understated piece with quieter dynamics on the piano.

This is contrasted with the burlesca that opens up in a dramatic fashion with a quick arpeggiated chord followed by some fast flowing lines complete with baroque ornaments and some quite exciting rising sequences that add drama to the music. Very nice.

Scherzo – The name of this movement is a surprise to me: I had it in mind that the Scherzo as a piece of music was more of a late classical or romantic invention. Essentially this is a lively rhythmic motif that Bach explores in this short piece that’s a minute in length.

Gigue – Dance-like triplet feel in 12/8 with some quite catchy moments with rising sequences, circle of fifths sequences and the familiar polyphonic texture.

In the same interview as above it turns out that these partitas were the first group of works that J.S.Bach published when he was in Leipzig. They were published in 1727 (IMSLP) and consisted of 6 keyboard partitas under the title Clavier-Ubung, ‘apparently in acknowledgment of the work of his predecessor as Thomas-Kantor in Leipzig, Johann Kuhnau, whose two sets of Clavier-Ubungen had appeared in 1689 and 1692′ (Liner notes Naxos CD 8.550312, David Nelson). I have heard of Kuhnau and indeed I have played at least one work of his on the piano, but didn’t know that he was Bach’s predecessor in Leipzig.

Also of note is the changing meaning of the word partita as the liner notes go on to explain: The choice of the word partita as a title for the suites that form the first volume of the Clavier-Ubung again echoes Kuhnau, whose Neue Clavier-Ubung had consisted of seven Partiten, a use of the word that was to become current in Germany, although originally it seems to have been used in Italian to describe sets of variations…’ (Liner notes Naxos CD 8.550312, David Nelson)

Cantata

Bach, Johann Sebastian

Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen!, BWV 51 (Praise God in all lands!)

http://imslp.naxosmusiclibrary.com/streamw.asp?ver=2.0&s=167137%2Fimslpcomp01%2F711

(Accessed 24/04/18)

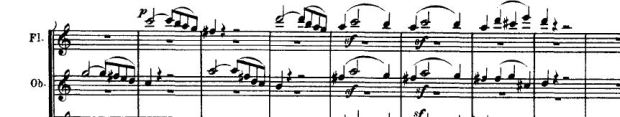

Scored for Trumpet, 2 violins, viola, soprano, basso continuo.

Gets off to a lively start in the aria, trumpet sounding repeated notes in a quasi-pedal fashion, closely following the 1st violin part, and this occurs throughout the first movement. My initial momentary reaction to the singing (as anyone who read my opera blog will know) was not good and I was anticipating the warbling… However, I very much enjoyed the singing – it’s quite a tune and in this instance I like the mellismatic style of singing and the lively accompaniment. It’s proper foot-tapping stuff.

Change of mood for the recitative as a more plaintive feel is conveyed by the slower tempo and sparser texture of voice, organ, and cello.

The next aria starts off with quiet organ and a cello arpeggiating its way through what sounds like a circle of fifths progression in a similar texture and tempo to the previous recitative. It sounds structurally as if it might be a chaconne but on reading some analyses it is described as a ‘basso quasi-ostinato’ (http://www.bach-cantatas.com/Pic-Rec-BIG/Suzuki-C30c%5BBIS-SACD1471%5D.pdf).

The chorale brings a lighter change of mood with more emphasis on the two violins which then segues into the finale with a return to the more mellismatic singing and bigger texture as the trumpet joins the fray once more.

The liner notes of the Naxos CD state that this cantata was written for performance on the fifteenth sunday after Trinity, possibly 17th September 1730, in Leipzig. However other sources suggest that it might have been performed for that occasion but that the work originated at a different time: ‘The scoring for solo trumpet, according to the customs of the Baroque era, was associated more with special festivities in church, public or court circles than with a regular Sunday service during Trinity…’ The demanding soprano part and the text of the cantata also point to a work that was composed for an altogether different occasion, possibly the Weissenfels court. Bach composed a number of cantatas for the Duke Christian of Sachsen-Weissenfels and he may have used this one on different occasions. Sometimes an over-worked composer has to take shortcuts!

References:

Click to access Suzuki-C30c%5BBIS-SACD1471%5D.pdf

Liner notes from Naxos CD 8.550643 – Keith Anderson

Mass

Machaut, Guillaume de (c1300 – 1377)

La Messe de Nostre Dame

http://imslp.naxosmusiclibrary.com/streamw.asp?ver=2.0&s=167137%2Fimslpcomp01%2F8595

(Accessed 25/04/18)

I know that this is an important work in the history of Western music but I wasn’t too sure why. It was composed in the early 1360s. Burkholder et al state that ‘La Messe de Nostre Dame was one the earliest polyphonic settings of the Mass Ordinary, probably the first polyphonic mass to be written by a single composer and conceived as a unit’. Machaut was both a poet and a musician and had the support and patronage of John of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia, and subsequently his daughter and other patrons. He settled in Reims in 1340 and worked as canon of the cathedral. Machaut seems to have been exceptional in the sense that he had an idea of his own creative worth and made efforts to preserve his works for posterity – and had the resources to do so. He lived during the ‘Ars Nova’ (New Art) period, named after Philippe de Vitry (1291 – 1361) who wrote, or at least was partly responsible for, a treatise on the new French musical style – something I will likely explore further in the ‘dissonance in music’ section.

Kyrie – All male choir, 4 voices, polyphonic, long held notes, mellismatic, with the ‘Triplum’ voice having the most ‘lively’ part. Certain difficulty in following the score.

Gloria – There is more ‘rhythmically together’ singing in the Gloria compared to the Kyrie where I would describe the parts as being more independent. Some interesting harmonies and cadences and generally livelier than the Kyrie with examples of hocketing towards the end. Mix of time signatures throughout the score: 2/2, 3/2, 4/2. This also occurs in the Credo.

Credo – Starts with a single bass voice enunciating ‘Credo’, though my score does not reflect this (also in the Gloria), further confusing me initially! More interesting cadences and harmonies.

Sanctus – seems to me like the Kyrie in the way the voices move.

Agnus Dei – In ‘perfect’ 3/2 time throughout.

Ita Missa Est – Also in 3/2 with the same interesting cadences and harmonies. The final cadence Em (rootless Cmaj7?) to F (without the 3rd) complete with parallel 5ths!!! In fact, looking at the other parts of the mass I notice that the Sanctus ends in a very similar cadence. The Gloria and Kyrie also finish with parallel octaves and 5ths!

I enjoyed listening to this – very unusual to my ears and definitely not something I would normally to – unless I was doing a music course 🙂

There are also examples of Isorhythms in this work. What this means is that the rhythm of the parts repeat, but the notes in the rhythm change. e.g. in the Agnus Dei bb31-46. The rhythm of each part repeats every 3 bars in this instance.

References:

Click to access MachautIsorhythmAll.pdf

Burkholder, J. P., Grout, D. J., & Palisca, C. V. (2014). A history of western music (Ninth edition.). New York, N.Y.: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc..

Sonata da Chiesa

Corelli, Arcangelo

Sonata a 3 in F Major, Op. 1, No. 1

http://imslp.naxosmusiclibrary.com/streamw.asp?ver=2.0&s=167137%2Fimslpcomp01%2F3496018

Very short slow opening movement to this sonata. Indeed the whole sonata is just 6 minutes long. Delicate violin lines with echoed fugal like motifs at times, with gentle accompaniment provided by lute. Just 2 violins, cello and lute. Slow-fast-slow-fast tempo to the movements. It’s all very tuneful stuff and ‘suitable’ for performance in church.

Corelli’s set of 12 trio sonatas were published in 1681. According to the liner notes these trio sonatas ‘became an important landmark in the development of Western classical music…It was through this set and his subsequent 5 operas that Corelli established himself as of the most celebrated and influential composers in Europe’. They were published by the Roman publisher Giovanni Angelo Mutij and subsequently published around Europe and remained in print throughout the 18th century. They have been described as ‘sonata da chiesa’ though Corelli never referred to them as such, but rather used the term ‘sonata a tre’, and they were not conceived specifically for church. Corelli followed these up with another set of trio sonatas, the Op.2 of 1685, which are of the ‘da camara’ type. Another point of note is that there some doubt about quite which bass instrument Corelli intended to be used. The bass part was originally written for ‘violone’ or archlute, but ‘violone’ did not refer to to the violoncello but some kind of bass violin though there were at least 3 different sizes of bass violin at the time.

Liner notes Linn CD CKD414, Simon D.I. Fleming.

Sonata da camara

Corelli, Arcangelo

Sonata, Op. 2, No. 4

http://imslp.naxosmusiclibrary.com/streamw.asp?ver=2.0&s=167137%2Fimslpcomp01%2F4852959

(Accessed 25/04/18)

Use of the harpsichord as the continuo in a sedate and rather melancholic Adagio opening movement.

Second movement Allemanda: Lively second movement where the violin and continuo set out a sprightly motif that lays the foundation to the Allegro movement. The rhythmic motif is echoed through the first Allegro section. This is then quickly followed by a Grave and adagio sections where muted arpeggios are laid out by the harpsichord with long legato violin lines on top.

Giga – Dancelike final movement

Particularly like the opening to the Allemanda and the muted harpsichord that follows, though the mute is only on for the very short Grave before the Adagio proper.

Passacaglia

Handel, George Frideric

Passacaglia / Keyboard Suite No. 7 in G Minor, HWV 432

http://imslp.naxosmusiclibrary.com/streamw.asp?ver=2.0&s=167137%2Fimslpcomp01%2F6348

(Accessed 26/04/18)

I first heard this Passacaglia last year, in-built on an electronic piano keyboard as an aid for learning. It spurred me on to listen to the whole suite and buy the sheet music.

The piece is based on a four bar pattern consisting of a descending circle of fifths in different inversions Gm – Cm – F – Bb – Eb – Adim – D – Gm.

Dotted chordal opening of the Passacaglia, followed by a similar dotted rhythm of of the right hand with a walking-bass accompaniment in octaves, followed by an arpeggio of the chords in the right-hand… Essentially the same chord progression is explored in different playing styles.

The passacaglia is taken from suite number 7 in G minor which was part of a collection of 8 great suites first published in London in 1720. Handel himself explains why he wishes to publish the suites:

‘I have been obliged to publish some of the following lessons because surreptitious and incorrect copies of them had got abroad. I have added several new ones to make the Work more usefull which if it meets with a favourable reception: I will still proceed to publish more reckoning it is my duty with small talent to serve a Nation from which I have receiv’d so generous a protection’. (Handel – Eight Great Suites, Book II: Suites Nos 5, 6, 7 and 8. ABRSM publications 1986 ISBN 978-1-85472-297-3).

Handel assembled the eight suites from a variety of mainly older material. Nos 1, 4, 5 and 8 already existed as dance-suites whereas part of the no.7 suite (a former prelude, the andante and the allegro) along with suites 2 and 6 were originally Italianate sonatas and contain very few dance forms. The full eight suites indeed provide contrasting examples of the French and Italian styles.

References:

Liner notes from Naxos CD 8.550416, Alan Cuckston.

Introduction by Richard Jones: Handel – Eight Great Suites, Book II: Suites Nos 5, 6, 7 and 8. ABRSM publications 1986 ISBN 978-1-85472-297-3.

Also a version for cello and violin: